The fall of the Roman Empire was not a single sudden event, but a prolonged process that unfolded over centuries. Its decline resulted from a complex combination of political, economic, social, and military pressures that gradually weakened the empire’s ability to maintain internal order and defend its vast territories. While historians often debate the exact causes, a careful study reveals that Rome’s collapse was the result of long-term systemic vulnerabilities, compounded by external threats. Understanding how the empire fell not only explains the end of Roman political authority in the West but also offers insight into the endurance of its culture, law, and institutions long after formal governance ended.

The empire’s decline can be traced through a series of interacting factors, each of which eroded the foundations of Roman power. Political instability, social fragmentation, economic weakness, and relentless military pressure combined to make the Western Empire increasingly fragile. Even though the Eastern Empire, later known as Byzantium, survived for another millennium, the fall of the West marked a profound transformation in the political and cultural landscape of Europe. By analyzing the mechanisms behind Rome’s fall, it becomes clear that no single event caused the collapse, but rather the accumulation of weaknesses over centuries.

Political Instability and Leadership Crises

Rapid Succession and Civil Strife

Political instability was perhaps the most visible symptom of Rome’s decline. From the third century CE onward, the empire suffered frequent changes of emperors, many of whom came to power through assassination, rebellion, or military coup rather than legitimate succession. Historians often refer to this period as the “Crisis of the Third Century,” when more than 20 emperors ruled within fifty years. Each regime change brought disruption, undermined administrative continuity, and encouraged rival generals to challenge authority. The constant turnover meant that policies were often short-lived, and long-term planning became almost impossible.

Civil wars became a regular feature of Roman politics. These conflicts were not limited to the capital or immediate surroundings; armies marched across provinces to enforce claims to the throne, often leaving destruction in their wake. Regions that had once been loyal to the central government became resentful or opportunistic, recognizing that military might, not legal authority, determined governance. The army, which had been a source of stability in earlier centuries, increasingly acted as a political instrument, with generals and soldiers pursuing personal advantage rather than defending the state. This blurring of military and political power weakened Rome’s internal cohesion and eroded public trust in imperial leadership.

Corruption and Administrative Overreach

As the empire expanded, its administrative apparatus became ever more complex. Governors, tax collectors, and local officials were required to oversee provinces, collect revenue, maintain infrastructure, and enforce law and order. Over time, the system became ripe for corruption. Many officials enriched themselves at the expense of the state and citizens, undermining confidence in government. Bribery, embezzlement, and nepotism were widespread, and enforcement of laws often depended on personal influence rather than formal authority.

The central government struggled to maintain control over distant provinces. Communication delays and logistical challenges made it difficult for emperors in Rome or Constantinople to enforce policies consistently. This created a growing gap between the elite ruling class and ordinary citizens, who often bore the brunt of taxation and labor obligations. Loyalty to the emperor weakened, as people increasingly relied on local rulers or military commanders for protection, further fragmenting political unity.

Division of the Empire

In an attempt to manage these challenges, Emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305 CE) introduced the Tetrarchy, dividing the empire into Eastern and Western halves, each with its own ruler. While this reform temporarily improved administrative efficiency and regional governance, it also laid the groundwork for long-term divergence. The Eastern Empire, centered on Constantinople, had a wealthier economy, stronger urban centers, and better defensive infrastructure. The Western Empire, by contrast, relied on a weaker economic base, had fewer resources for defense, and faced increasing difficulty managing distant territories.

Over time, the division created competing priorities and fragmented imperial authority. Cooperation between East and West was inconsistent, leaving the Western Empire particularly vulnerable to internal instability and external threats. This division of power, intended as a practical solution, ultimately accelerated the decline of the Western Empire.

Key Ideas — Political Instability

Frequent changes of emperors undermined governance and policy continuity.

Corruption and bureaucracy reduced public trust and efficiency.

Division of the empire produced unequal power between the East and West, weakening unity.

Economic Decline and Social Stress

Heavy Taxation and Financial Strain

Maintaining Rome’s vast bureaucracy, standing armies, roads, and urban infrastructure required enormous revenue. When territorial expansion slowed, the empire no longer had new sources of wealth to offset these costs. As a result, taxation increased, particularly on rural provinces, straining local populations. Heavy taxation caused resentment, reduced productivity, and occasionally prompted rebellion. The empire also faced inflation and currency debasement, as emperors minted coins with less precious metal to fund expenditures, further destabilizing the economy.

Economic inequality widened dramatically. Wealth concentrated in the hands of elite landowners, while small farmers, artisans, and urban laborers struggled to survive. Trade networks, once vibrant across the Mediterranean, faced disruption due to piracy, warfare, and declining infrastructure. As a result, the empire’s economy became increasingly fragile, with fewer resources available for public works, defense, or disaster response.

Decline of Agriculture and Urban Centers

Agriculture, the foundation of Rome’s economy, declined steadily. Soil exhaustion, over-reliance on slave labor, and rural depopulation reduced crop yields. Many small farmers were forced to sell their land to wealthy elites, who consolidated large estates but often failed to maintain efficient production. These changes undermined the traditional Roman middle class, which had previously supplied citizen-soldiers and local governance.

Urban centers suffered as well. Cities, once hubs of commerce, administration, and culture, faced population decline, reduced tax revenue, and deteriorating infrastructure. Public buildings, aqueducts, and roads fell into disrepair, weakening urban resilience. The decline of cities also eroded social cohesion, leaving citizens dependent on local landlords or mercenary protection rather than the central state.

Social Fragmentation

Rome’s social structure changed dramatically. The traditional middle class of small landowners disappeared, leaving a sharp division between wealthy elites and impoverished rural peasants. Many peasants became tied to the land as semi-serfs, while urban populations relied on state grain doles and charity. Loyalty to the emperor and central government weakened, as survival increasingly depended on local relationships and personal protection.

This fragmentation extended to the military as well. With fewer citizens available for recruitment, Rome relied on mercenaries and foreign soldiers, many of whom had limited loyalty to the empire. Social stress, combined with economic and military challenges, created a society increasingly incapable of supporting a large, cohesive state.

Key Ideas — Economic and Social Decline

Heavy taxation and inflation weakened the economy.

Agriculture and urban infrastructure deteriorated.

Social inequality and fragmentation eroded loyalty and the ability to sustain the state.

Military Pressure and Frontier Collapse

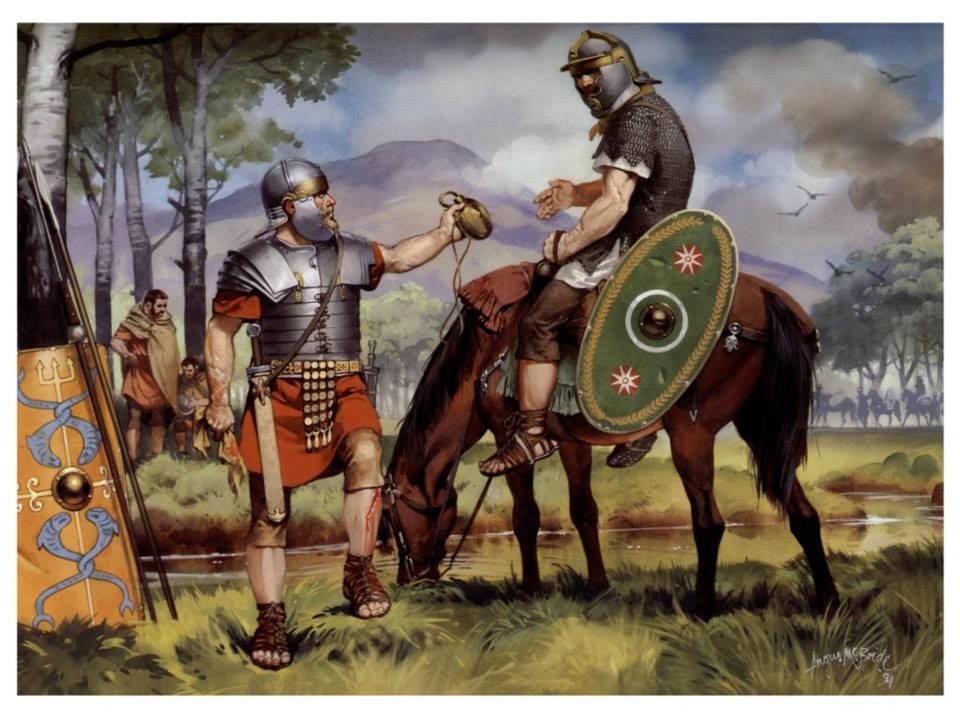

Reliance on Mercenaries and Non-Roman Troops

Rome’s military, once a citizen-based force, increasingly relied on mercenaries and foreign soldiers due to declining recruitment among Roman citizens. While often effective, these troops lacked the same cultural identity, discipline, and loyalty that characterized earlier legions. Generals commanding these armies sometimes pursued personal ambitions rather than coordinated defense, contributing to instability.

The reliance on outsiders also shifted the balance of power toward military leaders, who could exert political influence or even overthrow emperors. This trend undermined the traditional relationship between state and army, weakening Rome’s ability to respond effectively to threats.

Invasions and External Threats

From the late third century onward, Rome faced relentless pressure from external groups. Germanic tribes, Huns, Vandals, Goths, and other peoples repeatedly challenged imperial borders. The Western Empire lacked the resources to defend its vast territories effectively. Key regions, including Gaul, Hispania, and North Africa, were invaded, sacked, or abandoned, disrupting taxation, trade, and social order.

These pressures created a cycle of vulnerability: military defeats reduced economic resources, which in turn limited the empire’s ability to maintain a strong defense. By the fifth century, invasions had intensified, and Roman authority in the West was largely symbolic rather than practical.

The Fall of the Western Empire

By 476 CE, Western Roman authority had effectively collapsed. The last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer, marking the official end of imperial rule in the West. Governance fragmented into regional kingdoms, while Roman administrative and cultural systems persisted only partially. The Eastern Empire, centered on Constantinople, survived for nearly a millennium, illustrating that Rome’s collapse was regional rather than total.

Key Ideas — Military Pressure

Heavy reliance on foreign troops weakened cohesion and loyalty.

Continuous invasions destabilized borders and infrastructure.

The Western Empire collapsed under sustained external military pressure.